Conflict II

War of the Wizards?

I've heard it said that alot of our wars are caused by clashes between the New World & Old world Illuminati...

I'm not sure if the Rosicrucians, O.T.O., Autonomatrix & others are involved.

Military-Industrial Complex. If Ike couldn't handle them, we got our work cut out.

Another thing I've heard is that the Krupps pretty much own all those companies, no matter where they are located, this would explain why/how they all advertise at like Jane's.com, are at the paris Airshow etc.

The relationship between the military and industry. It was first described by President Eisenhower in his farewell address, where he warned of the irresponsible power of the military-industrial complex.

| US Military History Companion: Military]Industrial Complex |

has a clearly defined history. It was first used by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in his farewell address in January 1961, when he warned that “In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military]industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”The term soon came into widespread use because it seemed to fit and explain some of the new military realities of the time: the persistent high military spending in peacetime, which was unprecedented in American history; the persistent and costly arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union; and the persistent and seemingly pointless U.S. military involvement in Vietnam. The 1960s–1970s saw a flood of writings about the military]industrial complex, a flood that crested during the last years of the Vietnam War. By the mid]1980s, however, the term had largely fallen out of public discussion.

Whatever the ebb and flow of language, the concept reflects an enduring reality. Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the late eighteenth century, every great power has demonstrated a close connection between its military and its industry. Industrial development led to military advantage (e.g., the British steel industry and the Royal Navy) and military needs led to industrial development (e.g., the German Army and the German steel industry).

This military]industrial connection existed even in the commercial United States. Eli Whitney developed the mass]production process in 1798 while seeking a better way to manufacture U.S. Army muskets. For a century and a half thereafter, the U.S. government arsenal system was a military]industrial complex of the clearest and simplest sort.

The arsenal system was not the most common pattern of military]industrial relations in the United States, however. Normally, commercial demands first called an industry into being, and then the U.S. military, following the lead of the militaries of other great powers, applied the products of the new industry to military purposes. The expanding American steel industry after the Civil War soon found a market in the new steel]hulled U.S. Navy, but its major markets remained civilian. The next waves of American industry—successively the chemical, electrical, and automobile industries—also developed because of civilian, not military, demand.

Beginning in the 1930s and continuing through World War II and the Cold War, this pattern of civilian production leading military production was reversed. The next waves of American industry—aviation (later aerospace), computers, and semiconductors—were brought into being by military demand, and their products only later found civilian applications.

Two world wars reinforced the connection between the military and industry. In both wars, the largest defense contractors were the largest industrial corporations (in World War II, these included U.S. Steel, Bethlehem Steel, Dupont, General Electric, Westinghouse, General Motors, and Ford). However, when these wars were over (as after all previous U.S. wars), these American corporations quickly converted from production for military purposes back to production for commercial markets. With the minor exceptions of the U.S. government arsenals and shipyards, the military]industrial complex in the United States was a reality only in wartime.

A new kind of military]industrial complex came into being in the 1950s. The comprehensive national strategy presented in National Security Council memorandum No. 68, a call for Cold War, rearmament, seemed to legitimate, and the experience of the Korean War seemed to necessitate, a permanent military]industrial establishment, in peacetime as well as in wartime or at least in cold as well as hot war. After the Korean War, the Eisenhower administration did not undertake drastic reductions in military spending like the reductions after previous wars but rather maintained military spending at the level of about 10 percent of GNP. Much of this spending went for the procurement of weapons systems, especially aircraft and missiles. Moreover, several large corporations, particularly those in the aerospace industry, became completely dependent upon military contracts (e.g., Lockheed, General Dynamics, North American, McDonnell, and Grumman). Eisenhower himself presided over the institutionalization of the military]industrial complex that he would later warn against.

Many of the major military contractors were clustered in California and Texas. This concentration within particular states and congressional districts meant that their representatives in Congress became representatives of the contractors and of the military]industrial complex more generally. These representatives often became members of the House and Senate armed services committees, where they heavily influenced military procurement. The military]industrial complex thus developed into the “iron triangle,” composed of congressional committees, military services, and military contractors.

During the two decades of the greatest public discussion about the military]industrial complex in 1960–80, several arguments were put forward about its consequences for public policy: Some analysts argued that the military]industrial complex promoted military spending as the way to use fiscal policy to manage the national economy, a military version of the macroeconomic prescriptions of John Maynard Keynes. This led to persistent and massive federal budget deficits.

The Depleted Society

A related argument was that the military]industrial complex diverted resources from investment in long]run economic and social development into spending on nonproductive military weapons, depleting society instead of developing it. In particular, there were too many engineers devoted to developing military products and not enough developing commercial ones. This seemed to explain why Japan and Germany, which had much lower military spending per capita than the United States, were more successful in international commercial markets. This led to persistent and massive U.S. trade deficits.

The Follow]on System

It was also argued that, in order to preserve particular military contractors and their production facilities, the military]industrial complex promoted weapons systems that were merely new variations or “follow]ons” of previous systems from a particular production line. This led to a sort of technological stagnation.

The Gold]plating Syndrome

A related argument was that, in order to maintain the profits of military contractors, the military]industrial complex promoted excessive spending on superfluous features of weapons systems, often referred to as “waste, fraud, and abuse.” This led to fewer numbers of more expensive weapons.

Each of these arguments was highly controversial when first made. This is not surprising, given the high stakes in military expenditures that were involved. By now, however, most analysts of military procurement agree that there is substantial evidence supporting each as they apply to much of the period from the 1960s to the 1980s.

It was also argued, especially at the height of the Vietnam War, that the military]industrial complex put strong and persistent pressure on U.S. leaders to undertake military interventions and an adventurous foreign policy. Yet the evidence is largely against this argument. The U.S. military services, at least the army and the Marines, have consistently been reluctant to undertake military interventions. The military services generally have been in favor of the procurement of new weapons, but not the employment of them.

Whatever the power of arguments about the influence of the military]industrial complex on weapons procurement during the Cold War, they are much less relevant to the current era. The end of the Cold War and the fiscal constraints imposed by federal budget deficits brought an end to military Keynesianism. American society is certainly depleted in many ways, but its current problems do not include too little investment and too few engineers for commercial products. The follow]on system is less evident, since a major defense contractor (Grumman) was allowed to go out of business, and other production lines have shrunk greatly. There is still ample gold]plating—waste, fraud, and abuse—but it can now be seen as a sort of welfare system (like public works during the Great Depression) for a limited number of distressed localities.

A military]industrial complex still exists, but it is now a much smaller part of the U.S. economy than it was during most of the Cold War (military spending in the late 1990s is less than 3% of GNP). Because of this relatively small size, the military]industrial complex no longer seems to have consequences that are really damaging to American interests. The major problems now seem to arise from other complexes—perhaps the financial, medical, educational, or entertainment complexes—and from the complexity of America itself.

[See also Consultants; Economy and War; Industry and War; Procurement; Weaponry.]

Bibliography

- Mary Kaldor, The Baroque Arsenal, 1981.

- Thomas L. McNaugher, New Weapons: Old Politics: America's Military Procurement Muddle, 1989.

- Gregory Michael Hooks, Forging the Military]Industrial Complex: World War II's Battle of the Potomac, 1991.

- Ann Markusen et al., The Rise of the Gunbelt: The Military Remapping of Industrial America, 1991.

- Jacob A. Vander Meulen, The Politics of Aircraft: Building an American Military Industry, 1991.

- Ethan B. Kapstein, The Political Economy of National Security: A Global Perspective, 1992.

- Ann Markusen and Joel Yudken, Dismantling the Cold War Economy, 1992.

- Raymond Vernon and Ethan B. Kapstein, editors, Defense and Dependence in a Global Economy, 1992.

- John L. Bois, Buying for Armageddon: Business, Society, and Military Spending since the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1994

...

.

David Icke thinks all these blue bloods {Windsors included} are reptilian aliens

All the ancient gods of mythology etc. That's why the bigwigs interbreed...check it out, click on the image at left.

The Coming Holy Wars

Preachers of Doom

Christians who proclaim the coming apocalypse have failed to mobilize ordinary Americans but their views are shaping Washington's debate about Iran.

By Jeff Sharlet

Why are we so obsessed with the apocalypse? By "we", I don't mean those of us who actually believe in the imminent end of the world, as foretold by a literalist reading of the Bible (presumably a small share of this magazine's readers), but those of us who find apocalyptic believers - especially American apocalyptic believers - to be a source of sufficient anxiety that publishers churn out explanatory volumes such as Nicholas Guyatt's Have a Nice Doomsday: Why Millions of Americans are Looking Forward to the End of the World. Does the liberal-minded audience that Guyatt has in mind for what he refers to as his "unnerving" tour of the American apocalypse industry really believe the end is nigh?

How did we engineer this bullshit? As if reality wasn't hairy enough...

Praying for the Apocalypse

By Chris Hedges

The Gilead Baptist Church, outside Detroit, is on a four-lane highway called South Telegraph Road. The drive down South Telegraph Road to the church, a warehouse-like structure surrounded by black asphalt parking lots, is a depressing gantlet of boxy, cut-rate motels with names like Melody Lane and Best Value Inn. The highway is flanked by a flat-roofed Walgreens, a Blockbuster, discount liquor stores, a Taco Bell, a McDonald’s, a Bob’s Big Boy, Sunoco and Citgo gas stations, a Ford dealership, Nails USA, The Dollar Palace, Pro Quick Lube and U-Haul. The tawdry display of cheap consumer goods, emblazoned with neon, lines both sides of the road, a dirty brown strip in the middle. It is a sad reminder that something has gone terribly wrong with America, with its inhuman disregard for beauty and balance, its obsession with speed and utilitarianism, its crass commercialism and its oversized SUVs and trucks and greasy junk food. It is part of our numbing assault against community and connectedness. Ten or fifteen minutes of negotiating the traffic down South Telegraph Road makes the bizarre attraction of the End Times—the obliteration of this world of alienation, noise and distortion—comprehensible. The manufacturing jobs in the Detroit auto plants nearby are largely gone, outsourced to nations with cheaper labor. The paint is flaking off the cramped two-story houses that lie in ugly grid patterns off the highway. The plagues of alcoholism, divorce, drug abuse, poverty and domestic violence make the internal life here as depressing as the external one. And those gathering today in this church wait for the final, welcome relief of the purgative of violence, the vast, bloody cleansing that will lift them up into the heavens and leave the world they despise—the one that was devastated by corporatism—to be racked by plagues and flood and fire until it and all those whom they blame for the debacle of their lives are consumed and destroyed by God. It is a theology of despair. And for many, it can’t happen soon enough. The guru of the End Times movement is a small, elderly, gnome-like man with dyed coal-black hair, a battery-powered earpiece and a pedantic, cold demeanor. He is Timothy LaHaye, a Southern Baptist minister and the co-author, along with Jerry Jenkins, of the “Left Behind” series of Christian apocalyptic thrillers that provide the graphic details of raw mayhem and cruelty that God will unleash on all nonbelievers when Christ returns and raptures Christians into heaven. The novels are the best-selling books in America, with over 62 million in print. They have been made into movies, as well as a graphic video game in which teenagers can blow away nonbelievers and the army of the Antichrist on the streets of New York City. The global nightmare that leads to the end of history is a visceral and disturbing expression of what believers feel about themselves and our world. The horror of apocalyptic violence—the final aesthetic of the movement—at once terrifies and thrills followers. It feeds dark fantasies of revenge and empowerment. This theology of despair is empowered by widespread poverty, violent crime, incurable diseases, global warming, war in the Middle East and the threat of nuclear calamity. All these events presage the longed-for obliteration of the Earth and the glorious moment of Christ’s return. But until then believers are told they must battle Satan. And Satan comes in many guises. In churches across the United States believers are being girded for a holy war, one as self-destructive as that preached by radical Islam. “We are at war with the religion of Islam,” Gary Frazier, another popular leader, tells the crowd in the church outside Detroit, “and it is not a handful of radical Islamists who are taking over the religion and hijacking it. The fact is, ladies and gentlemen, today if you read the Koran, and any person who reads their Koran, the holy book of the Muslims, and believes what the book says, over a hundred times it calls for the putting to death of any person that does not embrace the teachings of Mohammed. “Can you explain to me how in the West that we would understand a person who would strap dynamite upon themselves and blow themselves up along with innocent men and women and children with the promise that they would have 70 brown-haired, I mean blond-haired, blue-eyed virgins for their unlimited sexual pleasure in this place called Paradise? And the parents of that person then throw a party celebrating the destruction of their child. You want to tell me you understand that kind of mentality? Because I don’t believe that. There’s no one in the Western world that can comprehend that kind of mind-set, but, ladies and gentlemen, that is the mind-set of the religion of Islam around the world. “Islam,” Frazier says dramatically, “is a satanic religion.” He warns of Muslim “sleeper cells” in America waiting to carry out new terrorist attacks. “You may have a Muslim doctor, and he may be a wonderful person,” he says. “He may love his family, but you know what’ll happen? One day, they will come to him—I’m just using this as an illustration—they will come to him and they’ll say, ‘We have a mission for you, and you will either do as you’re told,’ [or,] and they’ll whip out the pictures, ‘Here are your three children. We’ll send their heads to you in a box.’ Now, the difference is, is that if somebody told you that, you’d call the FBI or Homeland Security or somebody like that. They’re not going to do that. Do you know why? Because they know the Muslim will do just what they say, and when it comes right down to where the rubber meets the road, boys and girls, they’re going to save the lives of their own children before they’ll save your own. And you most likely would probably do the same thing yourselves.” He pauses and slowly scans the crowd, which sits silently, expectantly awaiting his next sentence. “I thank God for our men and women who are fighting over there because if they weren’t fighting there, we’d be fighting right here in the streets of America. I’m convinced of that,” he says, and the sanctuary erupts in loud applause. America, the crowd is told, is being ruled by evil, clandestine organizations that hide behind the veneer of liberal, democratic groups. These clandestine forces seek to destroy Christians. They spread their demonic, secular humanist ideology through front groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union, People for the American Way, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the National Organization for Women, Planned Parenthood, the Trilateral Commission and “the major TV networks, high-profile newspapers and newsmagazines,” the U.S. State Department, major foundations (Rockefeller, Carnegie, Ford), the United Nations, “the left wing of the Democratic Party” and Harvard, Yale “and 2,000 other colleges and universities.” All of these groups have joined forces, LaHaye has warned, to “turn America into an amoral, humanist country, ripe for merger into a one-world socialist state.” The radical Christian right has no religious legitimacy. It is a mass political movement. It is interchangeable, in many ways, with other traditional political movements ranging from fascism to communism to the ethnic nationalist parties in the former Yugoslavia. It shares with these movements an inability to cope with ambiguity, doubt and uncertainty. It also embraces a world of miracles and signs and makes war on rational, reality-based thought. It condemns self-criticism and debate as apostasy. It places a premium on action. It dismisses those who do not bow down before its god—and the leaders who claim to speak for God—as heretics and traitors. This movement shares with corporatists, who are busy cannibalizing our society for profit, the belief that there are a chosen few who know the truth and therefore have the right to impose it. The citizen, the individual, no longer has any legitimacy in this new world. All legitimacy is assumed by groups, whether they are corporate groups herding us over the cliff of globalization or religious groups that give popular vent to corporate-generated despair through faith in the Christian utopia. In this paradigm—corporate and religious—we become disempowered, afraid, passive and easily manipulated. Apocalyptic visions like this one have, throughout history, cowed populations and inspired genocidal killers. They have enticed societies into collective suicide. These visions nourished the butchers who led the Inquisition, the Crusades and the conquistadors who swept through the Americas converting and then exterminating the native population. These visions sustained the SS guards at Auschwitz, the Stalinists who consigned tens of thousands of Ukrainian families to starvation and death, the torturers in the clandestine prisons in Argentina during the Dirty War and the Serbian thugs with heavy machine guns and wraparound sunglasses who stood over the bodies of those they had slain in the smoking ruins of Bosnian villages. Those who promise to purify the world through violence, to relieve the anxiety of moral pollution and despair, appeal to our noblest sentiments, our highest virtues, our capacity for self-sacrifice and our utopian visions of a cleansed world. It is this coupling of fantastic hope and profound despair, along with visions of peace and light and absolute terror, of selflessness and murder, which frees the consciences of those who call for and carry out the eradication of those they have banished from moral consideration. When leaders of this movement, such as Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, sanction, as they do, pre-emptive nuclear strikes against our enemies, and therefore the enemies of God, they fuel the passions of terrorists in love with the same apocalyptic nightmares. They march us to our own doom cheered by the delusion that once the dogs of war, even nuclear war, are unleashed, hundreds of millions will die, but because Christians have been blessed and chosen by God they alone will arise in triumph from the ash heap. In this new world, where those who seek to do us harm will soon have in their hands cruder versions of the apocalyptic weapons we possess, dirty bombs or chemical or biological agents, the vision of those among us who welcome catastrophic warfare, indeed seek to hasten it, who fervently await the apocalypse and the end of time, who believe they will be lifted up into the sky by a returning Christ, forces us all to kneel before the god of death. The prayers these “Christians” near Detroit—and tens of millions across the nation—utter for deliverance and apocalyptic glory only hasten our flight from reality and ensure our self-annihilation. Chris Hedges, who graduated from seminary at Harvard Divinity School and was a foreign correspondent for nearly two decades for The New York Times, is the author of “American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America.”

...

If it had its druthers, our star Sol would bake us like a potato.

Personally, my questions never cease.

and most of the people i know or run into seem blissfully oblivious.

And they wonder why I smoke pot...lots of pot.

...

Baked to where I don't care.

......

Blow it up you bunch of assholes!

Can't be any worse than the numerous asteroid impacts the last 4.5 billion years.

An Islamic nuclear arms race? Jane's 23 August 2007

Despite years of negotiations and US sanctions, successive reformist and hardline Iranian governments continue to develop the domestic capacity to manufacture nuclear fuel through uranium enrichment, which can also be used to produce nuclear weapons. Iran's nuclear programme, combined with President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's bellicose rhetoric and the increasing influence of Tehran-affiliated Shia groups in Iraq, Lebanon and other Middle Eastern countries, has alarmed Sunni Arab regimes. Iranian officials insist their decades-long nuclear programme has entirely peaceful aims. They claim they need nuclear energy to provide additional civilian energy supplies in preparation for the day when their oil supplies become exhausted. Yet, foreign governments, including those in the Arab Middle East, suspect other considerations are also motivating the Iranian government to develop its own nuclear enrichment capacities. Having such a capacity could underscore Iran's claims to great power status, provide resources to benefit domestic political factions or, most worryingly, give Tehran the option to develop nuclear weapons more rapidly should Iranian leaders decide that circumstances warranted such a step. One response of these regimes has been to purchase additional conventional weapons from Russia, the US and other countries. Another has been to announce that they are considering launching their own nuclear initiatives. Although these governments formally deny that Iranian actions have induced their nuclear declarations, the near-simultaneous decision of so many Sunni Arab regimes to proclaim interest in pursuing some kind of nuclear energy programme raises the possibility of a nuclear arms race among the Islamic countries of the Middle East. In September 2006, Egypt became the first Sunni Arab regime in recent years to declare interest in developing a civilian nuclear power programme. President Hosni Mubarak and other Egyptian officials announced they would restart their country's programme, which has been in abeyance for two decades following the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster. Egypt faces growing water and electricity shortages, in part due to a soaring youth population, which a civilian nuclear programme could alleviate. Egypt currently possesses small nuclear research reactors, but is considering constructing at least one large power-producing plant. For example, one option being considered is inviting foreign companies to build a 1,000-megawatt plant at Al-Dabaa on the Mediterranean coast that would begin operating in 2015. Egyptian policy makers have discussed civil nuclear co-operation with the governments of Canada, China, Russia and the US.

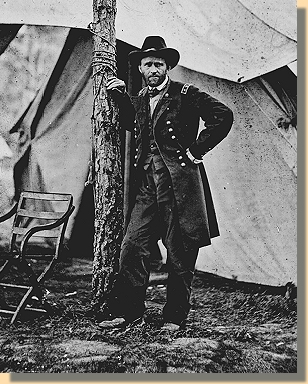

U.S. Grant:Father of Modern Warfare

Things were simplier when I was dogmatic Christian.

u

My favorite general.

Image title would go here.